“Dancing Fingers”

Innovating Piano Tuition

Introduction

In the final module of my Masters study, we were challenged to compare and constrast how innovation can be nurtured inside organisations and start-ups, and to show how an innovation programme could be implemented in an organisation or industry.

I chose to investigate the traditional and highly creative service industry of piano tuition.

Part one, a theoretical view and academic study on innovation, can be viewed here.

Part two, a study on the traditional industry of piano tuition, can be viewed here.

The Innovation Process Followed

All paths to successful innovation are unique and must adapt along the way in order to react to new learnings.

The steps taken were:

Identifyng the problem

Framing the problem

Research

Defining the problem to be solved

Setting Hypothesis and Ideation

Build, Measure, Learn - Lean Startup Iteration Process

Iterations

Recommendations for ongoing development

Identifying and Framing the problem

As with any big challenge, the initial problem is deciding where to start.

Piano tuition has remained largely unchanged since the piano’s inception, relying on a 1-1 relationship between a pupil and tutor. The pupil has to learn a range of complex tasks from developing keyboard techniques, read music, learn associated theory as well as develop musicality and performance.

The key challenge is to innovate and make learning the piano easier and quicker as well as to encourage fun for the pupil along the way.

Research with Professional Piano Tutor

Speaking to a specialist piano tutor led to gathering insights quickly. Ideally, more time would be spent with a range of teachers to get a broader perspective.

The study found that helping students practise in early stages of learning was a key area for further investigation.

Research - Interview with David Shire from Playground Sessions

Playground Session is a leading start-up company in teaching piano. A video interview was carried out with the founder of of the start-up based in New York.

David provided invaluable insight into the challenges of teaching piano and using technology. Playground Session are still very much in ‘startup mode’, but they are keen to establish their market and evolve their customers. Their focus is on providing great, relevant content and showing how to successfully play popular tunes. Technology provides great opportunities for self tuition, or when away from tutors, but currently has considerable limitations in giving accurate or high level or quality feedback.

The part of the study found that having fun and access to music liked by pupils is key.

Desk research

Many new inventions and technologies are emerging that might be adaptable for piano tuition.

Haptic learning technology enhances finger technique and assists practise. Though ‘gimmicky’, it is underpinned by scientific study.

Video technology, via personal cameras and video conferencing, could also enhance remote tuition, mentoring and practise.

The study found an ‘open’ approach to innovation and incorporating ideas from others may be a suitable strategy to follow.

Defining the problem to be solved

Following the initial phases of research and study I determined the focus should be on:

How Might We:

Help pupils be more accurate when the practise the piano by themselves but still have fun.

Ideation

Dancing Fingers is based on wearable vibrating tech and LED gloves which are connected to a teaching app and keyboard equipped with LED lights, thus optimising on latest haptic learning technology.

Fingering is already indicated by editors in most music scores

The fingers of the gloves vibrate individually to indicate which finger(s) needs to be used to play specific notes

Separate LEDs are displayed on the adapted keyboard indicating which notes should be played

These actions are co-ordinated by a central app which shows the pupil the score and notes to be played, together with a video and instructions for the hand and finger movement (adapted for Playground Sessions)

The app gives relevant feedback to help the pupil improve via a smart voice interface and on the app

The app is connected to an AI/Machine learning in the cloud. This gives feedback on musicality, which builds up in complexity from user records over time

The system also learns which music the user likes to play and recognises the ability of the user to makes relevant suggestions for new pieces to learn to play

Fun games and learning can develop around finger technique and playing

The aim of the product is to help users to:

Learn to use fingers correctly is like learning to dance with one’s feet.

Can build up finger strength, movement, coordination and playing efficiency

Haptic learning may develop into its own method of teaching as it stimulates the path between brain and hands faster

Setting Hypothesis

I used Maura’s Lean Canvas to capture initial hypothesis which were tested during user research.

This tool should be used throughout the Lean Start-up process and updated as new finding come to light about the product, the business and the customer

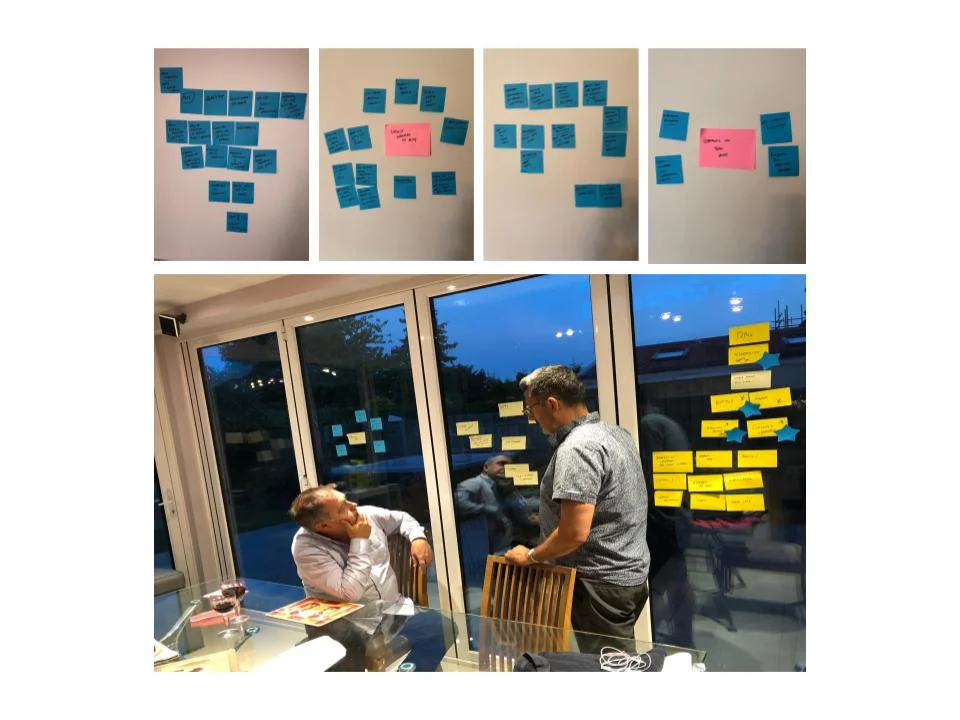

User Testing

A paper MVP prototype was created for user testing as follows;

Ecosystem - mapping of key technical architecture for digital and acoustic pianos

Glove/App/Interface - depicting how the gloves might work and operate with an adapted keyboard and interactive teaching app

Glove Designs - physical representations of how the gloves might look and perform.

1-1 interviews were then conducted at Enfield Arts Music School.

Pupils

John (Age 6)

Haroum (Age 9)

Davi (Age 10)

Maria (Age 10)

Teachers

Alvin - 25 years experience (See Fig. 30)

Paula - 30 years experience (See Fig. 31)

Paul - 30 years experience

Parents

Richard (Davi’s Dad)

Conclusion to Study

This study alone is not conclusive enough to recommend scaling the product development.

The MVP was limited in complexity and was insufficient to convey the concept or benefits to respondents, who approached the gloves with scepticism. However, the testing of gloves with just “numbers on” was successful in the small sample group surveyed. These gloves could be seen to help improve learning finger control. This would need to be validated with a larger sample.

Whilst academic studies show that haptic learning is a phenomena that can help with learning the piano, further verification is needed to show how this can be adapted and utilised within a commercial piano tuition programme.

Further investigation around customer development is required as ‘visionary customers’ success were not identified (Blank, 2013). Although interviews with traditional teachers and pupils in a typical surrounding were useful, the target audience for this product may lie with ‘self-teaching’ beginners which may be more willing to adopt new technology.

Recommendations for Next Steps

As most respondents were not able to make the ‘leap of faith’ with the MVP, I woud recommend creating a “Minimum Lovable Product” (Dombele, 2018) for future testing, so that users can see and feel the gloves working in combination with an interactive app.

I would recommend approaching Thad Starner, pioneer of haptic learning (Huang et al (2008)), to investigate the science behind the gloves and to determine how this technology can be exploited fully.

Testing iterations of this product is challenging. “Where” we find a technology in the Gartner’s hype cycle, which characterises the typical progression of emerging technology, can influence the kinds of research questions we can ask, the information available about that technology and the research methods that can be employed on the technology at that stage.

Given the nature of the emerging haptic technology, I would hope that the concept is not be ‘killed off’ before relevant proof can be gathered (Martin, 2014) and should bravely persevere with this ‘revolutionary innovation’ (Brown, 2009).